Welcome to peterboyd.com

Peter D. A. Boyd

Ferns and Pteridomania in Victorian Scotland

Peter D.A. Boyd

Web version of

BOYD, P.D.A. 2005. Ferns and Pteridomania in Victorian Scotland. The Scottish Garden. Winter 2005. pp.24-29.

Ferns are a conspicuous feature of the Scottish countryside and help create much of the special atmosphere of our wild places and gardens. Bracken and other ferns clothe many Scottish hillsides and fringe the burns, contributing to their character, especially when displaying their autumn tints, while ferns that luxuriate in small damp glens give them a magical ambiance, appearing to cascade from the rock faces. Different species of ferns inhabit different habitats but they contribute immeasurably to the character of the Scottish countryside and our gardens.

Ferns belong to an ancient group of plants called Pteridophytes which includes ferns, clubmosses and horsetails. Ferns and their relatives are an important constituent of the present-day Scottish flora; also the fossil flora of the Carboniferous Coal Measures (about 330 million years old) of central Scotland and the Jurassic rocks (about 160 million years old) found near Brora, Sutherland and in the Inner Hebrides.

Much of the industrial wealth of Scotland in the 19th and 20th centuries was founded on coal which is largely made up of the compressed remains of ferns, clubmosses, horsetails and the now extinct seed-ferns. In life, many of the extinct pteridophytes grew into large trees, dominating the tropical swamp forest – many millions of years before the evolution of woody conifers and the flowering trees that we know today. The Victoria Park in Glasgow preserves the fossilised stumps of Carboniferous clubmosses.

By the late 1830s, the British countryside was attracting increasing numbers of amateur and professional botanists. It was a time when it was considered that studying the 'Natural Wonders of Creation' was an appropriate way of praising God. The study of flowers and other plants was considered to be fairly safe by the Church and could be pursued by mixed groups including men and women, whereas the study of animals was frowned upon as it might lead to embarrassing situations and 'unsuitable parallels' being drawn between the activities of animals and people!

New British plant discoveries were published in periodicals, particularly The Phytologist, which first appeared in 1841. Ferns proved to be a particularly fruitful group of plants for new records because they had been relatively little studied compared with flowering plants. Also, they were most diverse and abundant in the wilder, wetter, western and northern parts of Britain which were becoming more accessible through the development of better roads and, subsequently, in the late 1840s and 1850s, the railway network. Developments in printing also led to the production of cheaper illustrated identification books and tourist guides, which further encouraged botanising excursions.

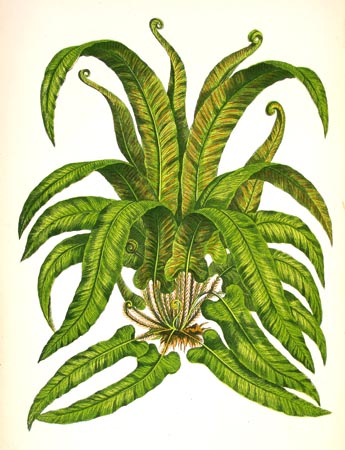

Hartstongue Fern Asplenium scolopendrium from Anne Pratt's Flowering Plants, Grasses, Sedges and Ferns of Great Britain c.1878. In spite of the simple basic form of the normal frond, the Hartstongue gave rise to about 300 frilled, crested, branching and other forms.

People of many different social backgrounds sought out the species and varieties described in the fern identification books to grow in their gardens or homes and to press the fronds in albums. Although there are only about 80 native British species and natural hybrids, the Victorians selected hundreds of varieties. Specialist dealers and fern nurseries developed that supplied not only native species and varieties but also exotic species from the Caribbean and other parts of the world.

'Gathering Ferns' (from the Illustrated London News July 1st 1871)

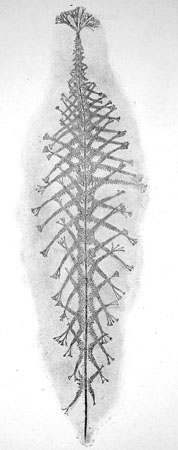

Those people with a serious interest in ferns were known as Pteridologists and could be said to be members of a fern cult rather than followers of a craze or fashion. They particularly sought odd variants of the wild species – unkindly named 'monstrosities' by the botanists of the time. Writers such as E. J. Lowe published books illustrating every variation (even if many of them turned out to be inconstant or never existed as more than one plant) and many attractive and graceful forms were discovered. Two of the most attractive monstrosities were 'crested' forms of several species such as the male fern and lady fern and 'crisped' forms of the hart's tongue fern. Although most of the cultivars of British ferns that are still in cultivation were originally found in south-west England or the Lake District, one of the most unusual and famous variations in any British fern was found in Scotland. This is a cruciate form of Athyrium filix-femina (lady fern) found in 1861 near Drymen, by Loch Lomond and named 'Victoriae' in honour of Queen Victoria.

Lady Fern Athyrium filex-femina (normal, crested and cruciate). A. filix-femina 'Victoriae' was an extraordinary Scottish find, shown in the third picture as a much-reduced 'nature-print'. From Druery's British Ferns and their varieties (1910)

The first British Pteridological Society started life as the "West of England Pteridological Society" in about 1873. However, a new pteridological society was formed in the North of England at Kendal in 1891 that, later, became the present British Pteridological Society – with many Scottish members.

The 50 year period between 1841 and 1891 saw the British Fern cult pass through four phases with changes of emphasis from (a) collecting British fern species, to (b) collecting new varieties of those species in the wild, to (c) raising new varieties from spores of sowings of those varieties already discovered, to (d) raising crosses between varieties by sowing mixtures of spores. New varieties were exhibited at local, regional and national horticultural shows.

Most species of ferns favour damp, shaded growing conditions. This made ferns particularly suited to grow in poorly lit Victorian homes so long as they received adequate moisture. However, people in large towns and cities could not succeed in growing ferns in their gardens or houses because of the dreadful air-pollution from coal fires and gas fumes until the introduction of the glazed case (Wardian Case) in the late 1840s. These cases not only excluded poisonous fumes but also maintained high humidity essential for many species. A wide variety of these Wardian Cases were made during the 1850s and later, some being very ornate, but few have survived. Various types of outdoor and conservatory ferneries were also popular and some structures have survived in old gardens even though, in most cases, the ferns themselves have not. However, the author has discovered old Victorian fern varieties previously thought to be extinct surviving in some old gardens. Spectacular Victorian and Edwardian ferneries, such as the Ascog Hall Fernery on the Isle of Bute, have been restored in recent years.

A simple glass dome used to grow ferns in a damp, pollution-free atmosphere. From Shirley Hibberd's Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste (1856)

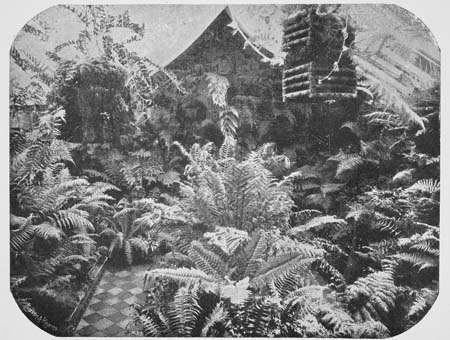

A conservatory fernery c.1900 with mainly cultivars of native British ferns, planted in the walls as well as the ground and containers. Athyrium filex-femina 'Victoriae' is planted at ground level at the end of the tiled path. From Druery's British Ferns and their varieties (1910)

By 1855, Charles Kingsley had recognised the prevalent passion for ferns as a phenomenon and in the course of encouraging the study of natural history in his book Glaucus, coined the term 'Pteridomania', meaning 'Fern Madness' or 'Fern Craze'.

Within a few years of 1855, Pteridomania gave rise to an ever-expanding range of home-made and manufactured 'fancy work' and other decorative items, with the fern motif appearing on almost every sort of object from christening presents to buildings, gravestones and memorials. Ferny decoration was available from birth to death!

No other single craze affected so many Victorians or such a cross-section of Society. Even the farm labourer or miner could have a collection of British ferns collected from the wild, and a common interest sometimes brought people of very different social backgrounds together.

Ferns could be used for decoration in ways that most other plants could not. Many species have fronds that adapt particularly well to representation on flat or curved surfaces in a variety of materials. Indeed, the fronds themselves could be pressed and dried to be used as stencils for spatter-work, inked for nature-printing, applied directly to paper as a specimen in an album or glued to two and three-dimensional objects to create a decorative effect. Even when the representation was stylised such as was common on engraved glass and metal, the effect was still recognisably 'ferny'.

The initiation of quantity production of manufactured ferny objects in the late 1850s commenced only after the botanical and fern cultivation aspect of the craze had already been active for some years. Fern designs on pottery, glass, cast-iron and other materials were prominent at the London International Exhibition of 1862. However, a whole generation had already been affected by botanical and horticultural pteridomania, which continued during the 1860s, and the fern motif was to remain popular, as a fond symbol of pleasurable pursuits, for the following 40 years or so.

Detail from damask table-cloth with fern decoration (private collection)

While many ferny objects were manufactured in England, Scotland specialised in the production of certain types of item.

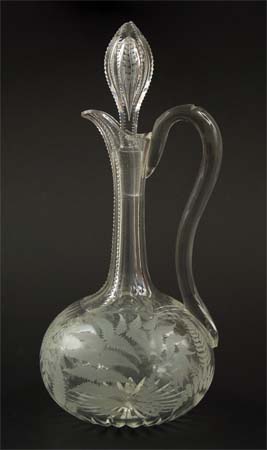

Glass engravers embraced fern decoration at an early stage. A wide selection of glass made at the John Ford Holyrood Glassworks, Edinburgh and engraved at the workshop of John Millar was displayed at the 1862 International Exhibition. Millar was one of a number of glass engravers who emigrated to Edinburgh from Bohemia during the 1850s. Although fellow Bohemian immigrants initially staffed his workshop, he soon began to train Scots in the techniques. The relationship between the John Ford Glassworks and Millar (and possibly other Edinburgh engravers) was extremely fruitful; an undated John Ford Catalogue (post 1868) contains page upon page of fern-decorated glassware. Another famous Bohemian engraver of ferns who moved from Edinburgh to Glasgow in 1873 and worked for W. & J. A. Bailey of Alloa was Emanuel Lerche. Some of the finest ferny glass was engraved during the 1880s. Glassworks in other parts of the British Isles also produced fern designs through engraving, acid-etching, sand-blasting and other techniques but the quality of most was not as fine as the 'Scottish' engravers and some depictions of ferns, especially those produced towards the end of the century were very stylised.

Glass decanter with engraved ferns, probably made at the Edinburgh glassworks c. 1870 (private collection)

Amongst the most attractive types of ferny objects are those in which actual fern fronds have been utilised in their manufacture. In some, usually home-made, fern fronds were pressed and dried, glued to a box or screen and varnished. In others, the fronds were used as 'stencils' with ink, paint or dye spattered or sponged over the fronds onto paper, textiles or wood. Some pottery was decorated using fronds in the 'leaf resist' technique and a variety of objects could be decorated by 'inking' a frond and using it to produce 'nature prints' on paper, cloth or other materials.

Mauchline Fernware Plate including a crested fern frond (private collection)

The Scottish wooden wares now known collectively as 'Mauchline Ware' (after Mauchline in Ayrshire, where much of it was made) include 'Mauchline Fernware'. Many items were actually made at the Caledonian Box Works in Lanark and elsewhere. Several different techniques were employed to produce such Fernware from about 1870 to the early 20th century. One involved using real fern fronds or parts of them, the leaves of other plants with fern-like foliage and other leaves such as field maple, sycamore, rose and ivy. After pressing, the leaves were attached in layers by tiny pins to the wooden box or other item that was to be decorated and brown or coloured dye was spattered over the leaves and wood, the leaves acting as stencils. Some leaves were removed and more dye spattered over the remaining leaves and object. This process was carried out several times to produce a three-dimensional effect with different densities of dye. The last leaf removed left the palest colour and an effect of layering of leaves that is the opposite of what was actually carried out. Other types of Mauchline Fernware used printed paper resembling the brown spatter-work technique glued to the item, objects with coloured transfers depicting fern species and varieties in reduced form and, more rarely, plain wood items bearing a photograph of ferns.

Mauchline Fernware Face-fan with ferns and Selaginella (private collection)

Many ferny ceramics and other items supplied to Scottish fern lovers were made in England or elsewhere. Although the Carron Foundry in Falkirk made cast-iron garden seats it could not compete with the range of ferny items manufactured by the Coalbrookdale Company in Shropshire, whose catalogue of 1875 included not only 'Fern and Blackberry' garden seats (often found in old Scottish gardens) and others depicting the royal fern (Osmunda regalis) but also ferny cast-iron umbrella-stands and fire surrounds.

Coalbrookdale Fern & Blackberry cast-iron Garden Seat c.1870 [Courtesy Shrewsbury Museums Service]

An infinite variety of items in almost every material one cares to name were made with the fern motif and, now, after reading this article, you may find yourself noticing ferns depicted on all sorts of Victorian objects and buildings in Scotland.

Carved stone ferns on a Victorian building in Elgin, Scotland

Oak Fern Gymnocarpium dryopteris in a Scottish garden

FURTHER READING

The Victorian Fern Craze: A History of Pteridomania. By D.E. Allen. Hutchinson, London. 1969

The Victorian fern cult in south-west Britain. By P.D.A.Boyd. In Fern Horticulture: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. By Ide, Jermy and Paul. Intercept, Andover. 1992. pp.33-56. Proceedings of the British Pteridological Society Centenary Symposium held in 1991. Abstract available at www.peterboyd.com/ferncultsw.htm

Details of the British Pteridological Society may be found on the society website at www.nhm.ac.uk/hosted_sites/bps/. This site includes a list of private and public Scottish gardens where you can see collections of ferns.

Pteridomania: the Victorian passion for ferns. By P.D.A. Boyd. In Antique Collecting 1993; 28(6): 9–12.Web version available at www.peterboyd.com/pteridomania.htm

Mauchline fernware and the Victorian passion for ferns. By P.D.A. Boyd. Mauchline Ware Collectors Club Newsletter 1993; 24: 2–3.

The Collector's Guide to Mauchline Ware. By D.Tractenberg & T. Keith. Antique Collectors' Club. 1999.

The author can be contacted c/o Shrewsbury Museums Service, Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, Barker Street, Shrewsbury, Shropshire SY1 1QH Tel: 01743 361196 E-mail: peterboyd@shrewsbury.gov.uk

Unfortunately, The Scottish Garden magazine ceased publication after the Winter 2005 edition.

See Ferns and Pteridomania for more articles on this subject